When out-of-town friends pop in to Brooklyn for a visit and ask where they should go to eat, I have one answer for them: Tanoreen. The restaurant has the best Middle Eastern food you could ever eat in New York.

It’s in Bay Ridge, a neighborhood populated with many Arab-Americans that is located in New York’s southwest corner. Going to Bay Ridge is a trek if you live in the Brooklyn neighborhoods that are closer to Manhattan. But it’s worth it.

It’s true that Tanoreen is out of reach for those who don’t come to New York. But now, you don’t have to wait for a trip to the East Coast to taste the cooking of Rawia Bishara, the owner of the restaurant. (The co-owner is her daughter, Jumana Bishara.)

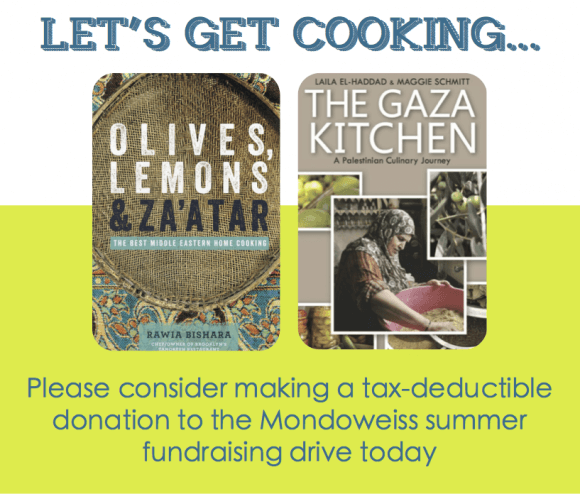

Earlier this year, Bishara’s book, Olives, Lemons and Za’atar: The Best Middle Eastern Home Cooking, was published. Filled with delectable recipes from hummus to brussels sprouts—a favorite of Tanoreen-goers—to eggplant napoleon and more, the book is bound to make your mouth water. And you can cook it on your own.

In late July, I had the chance to sit down with Bishara, a Palestinian who is from Nazareth, in northern Israel. We discussed why she wrote the book, the relationship of Tanoreen to Olives, Lemons and Za’atar and why family is so important to the author.

If readers donate over $80 to the website, our site will send you Bishara’s book of recipes (or, alternatively, The Gaza Kitchen: A Palestinian Culinary Journey). And if readers donate over $200, they will get a book and be invited to a delicious meal at Tanoreen with the Mondoweiss team later this year.

Alex Kane: My first question is simple. Could you explain to me how the idea for a book of recipes came about?

Rawia Bishara: I’ve been in the restaurant business for about 15 years, and through all those years, a lot of people have been asking me, “why don’t you write a book?” When I opened the restaurant, it was to honor my Mom and her recipes. And I figured [writing a book] would be a great way of doing it.

AK: And are the recipes based on your Mom’s cooking in Nazareth?

RB: Yes, most of the recipes are based on my mom’s cooking in Nazareth. That’s how I learned to cook.

AK: People who come to Tanoreen, your restaurant, will probably be familiar with at least some of the dishes, but not all. There are a lot of different dishes listed. How did you decide which types of food recipes to include?

RB: It’s really not every single one, and when I decided to open the restaurant and I made my menu, when I designed my menu, what was in mind—my Mom was the greatest cook—and I wanted to honor her and get all of this out. My Mom never cooked completely traditional. She was always creative and she always had her own way of slicing things and cooking things. And I figured I would take some thing that will honor her and at the same time honor the tradition that she comes from. Because the idea about our food, Middle Eastern food, is very, very misunderstood in this country and other countries.

When I came here close to forty years ago, people did not know anything about Middle Eastern food. And when they started finding out about Middle Eastern food, it was about falafel and hummus and shish kebab. And it’s really nothing compared to what we really cook and what we really offer. And I’ve seen Italian, Chinese and Japanese food become very successful. Everybody cooks their way and they bring food from their country—except us. And I wanted people to understand that we do have a very healthy, very beautiful tradition that puts families together around the table to eat, or to cook together in the kitchen. Usually cooking has a lot to do with culture: where you come from, what you are all about.

RB: In fact, it’s not after a village in Lebanon—it’s after a song from the very famous singer. Her name is Fairuz, and she sings to Tanoreen, which is a village in northern Lebanon. But it’s from a song. I don’t know that village.

AK: Understood. But you are from Nazareth.

RB: Right, I’m Palestinian. To me, it makes no difference, and I’m sure to some people it does. I’ve been asked that question. To me, all names are international, and these days it doesn’t make a difference what you call your son, what you call your daughter. I mean, we are Palestinians and we have many foreign names in our country. It’s not all Arabic names, and I think the song is very beautiful, and it’s just the name of a village that I heard is extremely beautiful.

AK: And there are connections between the food people eat in Lebanon and the food they eat in Palestine.

RB: All the Levantine area—Syria, Lebanon, Palestine—is very similar. In fact, I think all the Mediterranean, not just Middle Eastern, is similar. I went to Greece, I went to Spain four times, to many European countries, to France. We all have the same ingredients. It’s just the way we put it together, and the spices, is what makes it different.

AK: You touched on this earlier by mentioning your Mom. In your book, you include a lot of interesting stories about your family and eating with them. Could you explain the significance of those personal stories in a book otherwise about recipes?

RB: Recipes come from personal stories. It doesn’t come from the air. Something must have happened for a certain thing to become a certain way. I’m 100 percent sure of that. And if you grow up in a village, or an environment where they do everything from scratch, starting from making your own wheat to your own flour to your own tomato paste—all of these things—you will realize how much food is related to the personal and how much food is related to family and how much food is related to traditions and holidays. That’s how it comes about. And all these stories makes a life, and food is part of our life. It’s like 30 or 40 percent of our life, it’s very important. So it’s all connected.

AK: Olives, Lemons and Za’atar came out this year in March. What’s your take on the reaction to it, both among people who we would call “foodies,” and the general public?

RB: I’m extremely amazed at the success the book had. I wanted to write the book and I knew it was going to be published and sold, but we’re already in our fourth printing, and it’s fantastic. People tell me, or send me messages to our website and our e-mail, telling us how fantastic the recipes are, and how it’s easy to cook from it, and how everything is coming together and it tastes delicious. People are loving the pictures and are loving the culture and loving everything about the book.

AK: That’s great. The book is so vibrant.

RB: My children helped me. I would tell them what’s behind every recipe, what needs to happen, and they would help me put it together. That’s helped a lot. They know me very well and they know my family. So cooking is a connection between family, between kids, children and their parents. We are that type of people. We do sit together, we do cook together, we do shop together. It made it complete, and much better than if I had done by myself.

AK: Has there been a reaction in Nazareth to the book? I know it’s not translated into Arabic.

RB: Not yet, because it’s not even sold there. I just heard that it is being sold in Jerusalem. I’ve heard the reaction from the Palestinian side in the West Bank and Jerusalem. In fact, Ha’aretz published an article about it and we got a very good response from that too. But it’s not in the market [in Nazareth] yet. I think people would like to buy a book that is written in Arabic.

AK: Are there plans to translate it?

RB: Yes. From the beginning there was.

AK: Is the book also sold outside the US?

RB: It’s been sold everywhere. I heard it’s been sold in Australia, in the Arab countries. It’s been sold many places. It was published in England.

AK: The book is Palestinian, or Middle Eastern food, and obviously when people hear the word Palestinian, they think politics and conflict.

RB: But I don’t let them. It doesn’t interest me at all. I think cooking is politics. What I’m trying to do here—I wish everybody practiced politics like that. It’s spreading the culture. It’s showing the real face of us and who we are and what we are all about. And I think this is politics. My politics. I think when you speak politics, talk politics directly, you always create a challenge and other opinions. It’s different from accepting the other. Food is taste. They taste, they accept, and it goes from there. It’s as simple as that. I think this is the best way.

AK: I see in the restaurant there are signs for the book. Has the restaurant played a role, like hosting events for the book?

RB: It’s the other way around. The restaurant is very popular. It’s very well rated in Zagat and Michelin, and we got articles in the New York Times and the New Yorker. Everybody wrote about it. It’s extremely popular already. We’ve been in business for a long time and a lot of people tried the food, and those are the first people who bought the book. And it’s word of mouth. It starts spreading around. It’s people like you that makes it spread around more. It’s being talked about, and if people did not try the food and like it, I don’t think we would have had the same reaction to it.

AK: My last question is: if a random person came in, and they didn’t know about the book, what would you say to them to convince them to buy the book? Why should they buy it?

RB: Honestly, people come in and they eat and they tell me, “this is so delicious.” And I say, “why don’t you cook it?” And the guys on the floor usually ask me, “why don’t you have a cookbook?” “Why don’t you have cooking classes?” I’m always asked that question too. I do De Gustibus, the cooking school, on the eight floor of Macy’s. It’s quite popular. I do it twice a year, three hour lessons, and it’s always full. In general, I go out in my dining room every half an hour and I meet everybody that’s eating and talk to them and I see if they are doing okay, because this is part of feeding everybody.

AK: Is there anything I didn’t ask you that you think is important to say?

RB: The way I did the book, it’s for families to start giving some interest in buying some good, healthy food, cooking their own meals, spending time making it, and spending time eating it together. It is so extremely important that you put your family together on a dining table—lunch or dinner or whatever it is—whether you have little kids or older kids, because it brings a family together in a way that nothing else does. And it’s extremely important because we are losing family institutions. Family is a part of society. Whether we are here in New York or we are back in Palestine or in Nazareth or in Jerusalem or Los Angeles or Tokyo, this always keeps us in relation with our humanity. Being together, talking together, it makes us reach out. It makes us much better than everybody on his own Iphone, Ipad, or this or that, and it’s getting more and more—the loneliness, the separation in society, which I really don’t appreciate at all.

I’m talking about families being together. Get your stuff together. Buy it. Go home, sit down, have a glass of wine, cook together, eat together—you can’t believe the closeness, you can’t believe the feeling. I think it’s a very, very important part of society that people are losing. We need to get it back. If any cookbook helps, let’s do it through cookbooks.

Tanourine is the plural of tanour, the clay oven better known to some as the Indian tandoor. It’s also the name of an actual village in the Lebanese mountains named after the ovens in the Syriac language. The song in question by Fairuz is a’a hadir al-bosta, meaning “to the roar of the bosta”, which were buses like the old Blue Bird school buses that are still used as common transports between the Lebanese villages and rather folkloric by the people that ride them. Fairuz sings of the colourful ride she took on one of these buses between the villages of Himlaya and Tanourine and of the beautiful eyes of Alia; written for Fairuz by her jazz pianist son, Ziad Rahbani:

The Bus

I am promised with your eyes, promised

And if you only knew how many villages I crossed for them

You, you, your eyes are black

You don’t know, you don’t know

What they do to me, what they do to me, what they do to me

Your black eyes

On the roaring of the bus

Which was taking us

From the village of Himlaya to the village of Tanourine

I remembered you, Aliya, and I remembered your eyes

And damn your eyes, Aliya, how pretty they are!

On the roaring of the bus

Which was taking us

From the village of Himlaya to the village of Tanourine

I remembered you, Aliya, and I remembered your eyes

And damn your eyes, Aliya, how pretty they are!

We were traveling

In this killing heat

We were traveling

In this killing heat

One of the passengers was eating lettuce

And one was eating figs

There was one with his wife

And oh, how ugly was his wife!

They’re so lucky, the people of Tanourine

How empty their minds are

And they don’t know, Aliya, how beautiful your eyes are!

How beautiful they are!

On the roaring of the bus

Which was taking us

From the village of Himlaya to the village of Tanourine

I remembered you, Aliya, and I remembered your eyes

And damn your eyes, Aliya, how pretty they are!

We were riding

Riding without paying

We were riding

Riding without paying

Sometimes we would hold the door for the driver

And sometimes we would hold the passengers for him

And the one with his wife,

She got dizzy and fainted on his shoulders

I swear to you, if he had only seen how pretty your eyes are

He would have left her to go to Tanourine by herself

On the roaring of the bus

Which was taking us

From the village of Himlaya to the village of Tanourine

I remembered you, Aliya, and I remembered your eyes

And damn your eyes, Aliya, how pretty they are!

On the roaring of the bus

Which was taking us

From the village of Himlaya to the village of Tanourine

I remembered you, Aliya, and I remembered your eyes

And damn your eyes, Aliya, how pretty they are!

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=TeZBV1eGqbM

Mmm. Makes me hungry.

For those of you in the area, another great Palestinian restaurant and grocery is the Holy Land on North Central Ave in Minneapolis.

I always stock up on my za’atar and Palestine olive oil everytime I go.

Zaatar is another of Israel’s several cultural thefts of Palestinian patrimony. In 1977 it passed a law against the picking of zaatar in commercial quantities supposedly because it was becoming an endangered species, which was just another of Israel’s gimmicks to prevent Palestinians from earning a living. Israel is now claiming it as one of its national foods. Excerpt from the Columbia News service with photos of the green zaatar plant and the dried brownish version once dried and mixed with other herbs. :

“… In Israel and the West Bank, za’atar also has a sociopolitical resonance far beyond culinary and nutritive realms. It has been a protected plant since 1977, when Israeli legislation made it illegal to pick it in the wild. Environmentalists claim that overharvesting has nearly denuded Israel of wild za’atar, and offenders risk fines of up to $4,000 or six months imprisonment for picking commercial quantities.

In the U.S., as the popularity of za’atar is on the rise, and the spice is being revered for its distinctive taste. Little by little, za’atar is going mainstream. But in Middle Eastern homes, za’atar has a political significance that doesn’t cross borders.

Prior to the ban, za’atar already played an important symbolic role in Palestinian identity. Za’atar has been celebrated in the poems of the late Palestinian national poet Mahmoud Darwish and has been equated to “a symbol of the lost Palestinian homeland,” according to Omar Khalifah, a Palestinian-Jordanian Ph.D. candidate in Middle Eastern Studies at Columbia University.

Amidst the ruins of a historic Palestinian village near Jerusalem, za’atar and prickly pear grow in the wild. (Photo by Melissa Muller Daka/CNS)

Palestinians still forage for the herb in the wild because it remains an important symbolic role in their identity, said anthropologist Nasser Farraj, director of Palestinian Fair Trade, a company based in the West Bank that exports za’atar spice mixture. Farraj says the ban is a form of discrimination against Palestinians that has nothing to do with protecting the plant. “It is a political issue, definitely not an environmental one,” he says. The ban is a “land control and land access issue,” that has transformed the traditional foraging and consuming the iconic herb into an act of resistance against Israeli authority…”

for full article:

http://columbianewsservice.com/2010/02/the-spicy-politics-of-a-new-food-trend/

Walid, let me get this straight: by protecting the plant,( used a lot by Palestinians..)and saving it from extinction, Israel is discriminating against the Palestinians…Right?

“But I don’t let them. It doesn’t interest me at all. I think cooking is politics. What I’m trying to do here—I wish everybody practiced politics like that. It’s spreading the culture. It’s showing the real face of us and who we are and what we are all about. And I think this is politics. My politics. I think when you speak politics, talk politics directly, you always create a challenge and other opinions. It’s different from accepting the other. Food is taste. They taste, they accept, and it goes from there. It’s as simple as that. I think this is the best way.”

Amen. There is no better way to getting down to the business of being human than food. And food tells us our human story is interchange of everything, especially culture.

Though I forewent my book w/my MW donation, I will get a copy and I look forward to visiting when next Stateside.

Recently prime Minister Abe tried to wink at the rightwing of Japan by saying something about how he regrets Japanese people don’t eat enough Japanese food. Only problem for him and any other purist (because it works in almost every cuisine) is that every Japanese food item in the pantheon has its, often quite recent, origins somewhere else. And Restaurants in Japan serving Japanese food are disproportionately run by people of recent Chinese and Korean heritage.