Following the controversial termination of Steven Salaita’s hiring at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign (UIUC), the university’s Committee on Academic Freedom and Tenure (CAFT) initiated an investigation into whether the termination violated the university’s statutes and bylaws and academic freedom.

The CAFT issued its findings and recommendations in a report on December 23, accusing the administration and board of trustees of violating shared governance and academic freedom, and calling on the university to reconsider Salaita’s application and financially compensate him for his unjust termination.

This is the first of two articles exploring elements of the CAFT report. In this first article, I demonstrate how Salaita’s critics—the same ones who misrepresented Salaita’s tweets—are now misrepresenting the CAFT report.

In particular, I focus on the claims made by two prominent critics of Salaita: William Jacobson, who is the editor of the Tea Party Zionist blog Legal Insurrection, and Liel Leibovitz, senior writer for Tablet magazine.

As I mentioned in a previous article, Jacobson was the instigator of the Salaita affair who handpicked the initial set of tweets that, out of context, would portray Salaita negatively. Meanwhile Leibovitz justified Salaita’s firing in Tablet and attempted to challenge Salaita’s scholarship.

Both Jacobson’s and Leibovitz’s articles on the CAFT report are enjoying wide circulation among critics of Salaita, as the articles reinforce false claims made against Salaita and downplay the inconvenient findings and recommendations of the report.

Here I show that Jacobson’s interpretation of the CAFT report is distorted, complete with a false quote, intentional misreadings, out-of-context quotations, and unwarranted inferences.

Leibovitz’s review of the CAFT report is even worse. I demonstrate that Leibovitz has not even read the report, instead paraphrasing Jacobson’s article—complete with Jacobson’s misquote—and inserting even more factual errors based on a misreading of another misreading of the report.

I also address the extent to which the CAFT report confronts the issue of donor influence.

Contents

- “Legitimate concerns”

- Scholarship “almost indistinguishable from a political purpose”

- “Anti-Israel” and “anti-Semitic” tweets

- Limitations of the CAFT report: interviews

- A false quote from James Montgomery

- Limitations of the CAFT report: documentation

- The extent of donor influence

- “No evidence”

- Evidence of donor influence

- Are accusations of donor influence anti-Semitic?

- Conclusion

“Legitimate concerns”

In his December 23 article on the CAFT report, William Jacobson claims the report found that Salaita’s tweets had raised “legitimate concerns”—a phrase that Jacobson reproduces twice in quotes.

From the article’s subhead:

Tweets raised “legitimate concerns” as to fitness since Salaita’s scholarship “almost indistinguishable from a political purpose.” [all emphases throughout are mine]

And from the fourth paragraph:

The failure to call for restoration of position was based, in part, on the Committee finding “legitimate concerns” about whether Salaita’s anti-Israel (and some say anti-Semitic) tweets reflected on Salaita’s professional fitness, competence and care since his scholarship is “almost indistinguishable from a political purpose.” That political purpose, of course, is the destruction of Israel.

In fact the phrase “legitimate concerns” appears nowhere in the CAFT report.

Strangely, this false quote also shows up in Liel Leibovitz’s December 30 Tablet article on the report:

[N]ot only does the committee stop short of calling for Salaita’s restoration, it also cites “legitimate concerns” about whether Salaita’s anti-Israel expressions on social media make him ill-equipped to stand before a classroom.

Not only does Leibovitz reproduce Jacobson’s misquote, his entire sentence is a paraphrase of Jacobson’s fourth paragraph, without attribution.

At best, the CAFT report spoke of “legitimate questions,” which is distinct from “legitimate concerns.” The committee made a distinction between questions of “political acceptability,” which are illegitimate questions, and questions of “professional fitness,” which are legitimate:

There are circumstances where political speech can legitimately trigger inquiry into professional fitness, the question, however, being one of professional fitness, not political acceptability.

The committee determined that it was not legitimate for Chancellor Wise to raise questions about Salaita’s political speech. However, to the extent that those concerns translated to questions about his professional fitness, they could be legitimate:

[P]olitical speech, though rarely in itself evidencing professional unfitness, can give rise to legitimate questions – for example, whether Dr. Salaita’s passionate political commitments have blinded him to critical distinctions, caused lapses in analytical rigor, or led to distortions of facts. These are questions that have arisen in the present controversy.

The Chancellor, in providing the Committee with her judgment of the Trustees’ reasons for rejecting the appointment of Dr. Salaita, conflated political speech with professional speech. The former, we have concluded, is beyond the University’s remit to regulate. But the latter raises legitimate questions.

Note that the report only offers that legitimate questions “have arisen.” In other words, the committee determines that, strictly in the context of professional fitness, the administration makes a valid argument for consideration—but not necessarily that the argument is sound. A separate academic committee would have to determine the soundness, and it may only concern itself with the “questions that have arisen from the present controversy”:

Dr. Salaita’s scholarship has already been reviewed rigorously, according to all normal and appropriate procedures, so we allow only that his reviewers may not have attended to questions that have arisen from the present controversy.

Thus, in this context, the committee sought to determine whether “legitimate questions” were raised that would merit faculty review. It did not purport to place value on the legitimacy of the concerns themselves, which is why it is incorrect to translate “legitimate questions” into “legitimate concerns”—especially when the latter is not an actual quote.

Scholarship “almost indistinguishable from a political purpose”

According to Jacobson, the committee declared that Salaita’s “scholarship is ‘almost indistinguishable from a political purpose,’” and he adds that “That political purpose, of course, is the destruction of Israel.”

This is a deliberate distortion of what the CAFT report actually stated, and which was stated in the context of determining what would qualify as protected political speech.

The CAFT report cited a journal article that Salaita had submitted as part of his UIUC application, “The Ethics of Intercultural Approaches to Indigenous Studies: Conjoining Natives and Palestinians in Context.” Within that article, in a section on “Ethics and Indigenous Studies,” Salaita listed five ethical tenets to guide indigenous studies, of which the report cites one:

[Salaita] has stated that his address to the subject of his appointment, Indigenous Studies, is informed by certain critical ethical tenets, one of which is, for example, a “proactive analysis of and opposition to neoliberalism, imperialism, neocolonialism, and other socially and economically unjust policies, which not only affect Indigenous peoples most perniciously, but rely on Indigenous dispossession to fulfill their ambitions.” This tenet—almost indistinguishable from a political purpose—is taken by Dr. Salaita to be an intrinsic part of his work.

In other words, what the report cites as “almost indistinguishable from a political purpose” is not Salaita’s scholarship but rather one out of five ethical tenets that guide his work on indigenous studies.

Moreover the report does not assign a value judgment on that “political purpose”—much less claim that that political purpose is “the destruction of Israel.”

The report only seeks to classify the tenet as “political” in order to demonstrate how “the line between the political and the professional can blur”—since according to the committee, political speech is protected while professional speech is not.

This subject will be explored further in my second article on the CAFT report.

“Anti-Israel” and “anti-Semitic” tweets

Both Jacobson and Leibovitz suggest that the CAFT report made a value judgment on the political content of Salaita’s tweets. It did not. The CAFT did not suggest or even consider whether the tweets were “anti-Israel,” “anti-Semitic,” or that they called for “the destruction of Israel”—all claims inserted by Jacobson and Leibovitz in their interpretations of the report.

In fact, the CAFT steered clear of judging the political content of the tweets because it was ultimately irrelevant to their determination. To the extent that they do comment on the nature of the tweets, they merely refer to them as “unquestionably … strong sentiments and beliefs about controversial political ideas and events”:

For some, the tweets are offensive, hateful, and bigoted; for others they express desperate resistance in the face of unbearable oppression; and for yet others it is both … Regardless of the tweets’ tone and content, they are political speech – part of the robust free play of ideas in the political realm that the Statutes insulate from institutional sanction …

Yet Jacobson and Leibovitz misleadingly suggest that the CAFT found “legitimate concerns” about “anti-Israel” and “anti-Semitic” tweets that called for “the destruction of Israel.”

Limitations of the CAFT report: interviews

In his Tablet article, which was entitled “U. of Illinois: Donors Didn’t Derail Salaita Hiring,” Liel Leibovitz focuses on the committee’s statement that “no evidence” was found of donor influence.

Leibovitz challenges University of Chicago professor Steve Cicala, who had previously suggested that donor influence factored into Salaita’s termination:

Reached for comment, [Cicala] had little to say … misreading the report as simply relaying Chancellor Wise’s denials of donor influence—the committee went much further, examining emails and talking to other members of the administration and board of trustees…

Yet if Leibovitz had actually read the CAFT report, he would have known that the board did not cooperate in the investigation. From page 7 of the report:

As part of our investigation, we invited the Trustees to comment on the Board’s role in this matter and in particular on the meeting of July 24. Only one Trustee, James Montgomery, responded, and he referred us to the public comments he had already made.

Elsewhere, Leibovitz claims that the committee

spent considerable time interviewing the key players and reviewing reams of documents pertaining to the decision to refuse a tenure track position to Steven Salaita.

In fact, only one “key player” was identified in the report as having been interviewed: UIUC Chancellor Phyllis Wise, who was interviewed by the committee on one day, November 14.

So who else did the committee contact? According to the report, the committee had email correspondence with Virginia Tech Vice Provost Jack W. Finney, who was not a “key player.”

We also know that the legal counsel for the board of trustees reviewed part of the report before publication and provided the full contents of the report’s Appendix C and Document 10.

What about Steven Salaita or his counsel? According to Peter Kirstein, vice president of the Illinois AAUP,

I was able to independently confirm with multiple sources that the CAFT never contacted Dr. Salaita or his lawyers prior to releasing their document…

The committee may have interviewed other “key players,” but if so, they were not cited in the report, which relied overwhelmingly on Wise’s narrative. Thus Leibovitz has no basis to claim that the committee had “spent considerable time interviewing the key players” when the only key player interviewed and cited at length was Phyllis Wise.

The fact that Leibovitz would make claims about the report that are directly contradicted by the report itself, and the fact that he misquoted the report using William Jacobson’s exact same misquote, clearly demonstrate that Leibovitz did not read the report.

A false quote from James Montgomery

As further proof that Liel Leibovitz did not read the CAFT report, we can consider this completely incorrect passage from his Tablet article:

This assertion [that donors had no influence] is seconded in the report by James Montgomery, a prominent civil rights attorney and a university trustee who had cast the sole vote in support of hiring Salaita. (For more on the report’s intricacies on the donor question, read Steven Lubet’s excellent account).

In fact the report does not cite James Montgomery as having said anything about donors. Leibovitz appears to have misread Steven Lubet’s equally faulty blog post, where Lubet made reference to both Montgomery and the CAFT report in the same paragraph, though not in the same sentence.

In Lubet’s blog post, the somewhat close proximity of two nouns, “CAFT report” and “James Montgomery,” appears to have confused Leibovitz, who then mistakenly claimed that the CAFT report had cited Montgomery on the donor issue.

Moreover, Lubet himself is incorrect when he claims that Montgomery “denied that donor pressure was responsible for the majority’s decision.” Lubet cites as proof a brief interview that Ali Abunimah had conducted with Montgomery at the September 11 board meeting. Instead of denying donor pressure, however, Montgomery states that he is not familiar enough with the issue to say:

Abunimah: Many people have said donor pressure played a role. Do you think it played a role in how this has played out?

Montgomery: I can’t say to what extent donor pressure played a role because I’m not familiar with any of it except what little that I’ve read, and it only related to one donor [presumably referring to press reports about an unknown six-figure donor]. So I don’t know that that’s generally the case.

Since Montgomery was the sole trustee to vote in favor of Salaita’s appointment, his inconclusive statement can hardly be construed as an unequivocal denial of what led the administration and other trustees to reject Salaita.

Limitations of the CAFT report: documentation

Implicit in Leibovitz’s depiction of “reams of documents” reviewed and “the committee [going] much further, examining emails” is a suggestion that the CAFT was privy to considerable new or exclusive documentation. The report itself does not substantiate this assertion.

Almost all of the documentation cited or reproduced in the CAFT report came from publicly available and widely distributed information: UIUC press releases, statements made to the press, an online recording of a board of trustees meeting, and emails previously released through FOIA requests—including 443 pages of FOIA documents that I personally released to the public.

The counsel to the board of trustees also provided the committee with a hand-picked and slightly annotated selection of Salaita’s tweets.

On the other hand, there is no indication that the committee had access to any of the following:

- The minutes or recordings of the pivotal board of trustees executive session of July 24.

- The minutes or recordings of the board of trustees executive committee meetings of August 18 and August 22.

- Unredacted versions of the emails released through the FOIA requests.

- Pertinent emails not released through FOIA requests.

- The emails of the University of Illinois board of trustees pertaining to Steven Salaita.

These limitations do not invalidate the report—rather they help us determine the extent to which we should accept the findings made in the report, especially in circumstances where the report may have drawn conclusions without ample documentation.

However, the bulk of the CAFT report is concerned with applying university statutes and principles of academic freedom to the case at hand, which does not necessitate much on-site investigation. Thus much of the report’s citations refer to case law and precedent studies.

Such research, however, does not aid in the determination of specific details of the case, such as the extent of donor influence.

The extent of donor influence

Leibovitz claims that Steve Cicala had “misread” the report as “simply relaying Chancellor Wise’s denials of donor influence.” I have already demonstrated that Leibovitz himself did not read the report. In contrast, Cicala’s assertion can be easily affirmed.

In all of the 41 pages of the report (excluding the reprinted emails), reference to the donor claim comprises a total of three sentences in a single paragraph on page 6:

Many of these emails have been made public as the result of a Freedom of Information Act request, and the fact that some came from donors has been widely reported. The Chancellor has stated that donors in no way influenced her actions with regard to Dr. Salaita. This investigation found no evidence that they did.

Thus Cicala is correct: the only source on the donor issue that the CAFT report cites is Wise’s denial of any donor influence on her own actions.

Let’s look at the three sentences closer. The first sentence does not mention any specific charges of donor influence—only that it “has been widely reported” that some emails “came from donors”:

Many of these emails have been made public as the result of a Freedom of Information Act request, and the fact that some came from donors has been widely reported.

The second sentence introduces the concept of donor influence, but only in the context of Phyllis Wise’s denial, while the third sentence directly responds to that assertion:

The Chancellor has stated that donors in no way influenced her actions with regard to Dr. Salaita.

This investigation found no evidence that they did.

Taken in its most literal sense—which in the absence of further explication is all we can do—this is the extent of the report’s proclamation on the donor issue:

“This investigation found no evidence that” donors influenced Wise’s actions.

In other words:

- The report says nothing about the extent of donor influence on anyone other than Chancellor Wise.

- To the extent that the report says anything about donor influence on Chancellor Wise, it relies solely on Wise’s denial.

- The report neither claims to establish nor issues a determination that there was no donor influence. It merely says that in the course of “this investigation”—that is, an investigation that was not explicitly tasked with looking for evidence of donor influence—it “found no evidence” that Wise was personally influenced by donors.

- Beyond transcribing Wise’s denial, the report does not say to what extent it sought to determine whether donor influence was a factor.

- The report does not directly address or seek to refute any specific charges of donor influence. Instead it mentions in passing “the fact that some [emails] came from donors had been widely reported”—which is not a charge at all.

That the CAFT report fails to cite a single charge of donor influence raises doubts on whether the committee was ever engaged in investigating such charges. At the very least, one cannot claim that the report refutes charges of donor influence when it never spelled out those charges in the first place.

“No evidence”

For comparison, we can see that the phrase “no evidence” appears twice in the report—once in the context of donor influence and the other in the context of Salaita’s fitness for teaching, as follows:

[T]he Chancellor also suggested that Dr. Salaita’s tweets raise a question of his professional fitness, which in universities is judged primarily through teaching and scholarship …

Suffice it to say, there is no evidence that Dr. Salaita has functioned improperly as a teacher. As part of his application for employment at the University of Illinois, he submitted his teaching evaluations from Virginia Tech University, which indicate that he was well received as a teacher; there were no allegations of misuse of the classroom. Whether the current controversy that surrounds Dr. Salaita, or which might arise in the future, could affect his success as a teacher is pure speculation.

Here, the use of the phrase “no evidence” is unequivocal, and in contrast to the way it is expressed on the donor issue:

- Here, it cites the actual charge. On the donor issue, it does not.

- Here, it states firmly that “there is no evidence.” On the donor issue, it is careful to state only that “this investigation found no evidence.”

- Here, it follows up the statement of “no evidence” with evidence pointing to the contrary, then concludes by dismissing the charge against Salaita as “pure speculation.” On the donor issue, it says nothing else.

Compared to this usage of the phrase “no evidence,” we can see that the report was deliberate in its choice of words on the donor issue and implied nothing more than exactly what it stated in its three short sentences.

Evidence of donor influence

Wise’s denial of donor influence is nothing new. As reported by the press on September 2, Wise claimed that her decision on Salaita was influenced by no one at all:

I meet with foundation leaders, national and international university and corporate leaders, my fellow presidents and chancellors, and state and federal government officials. And, of course, I meet with alumni, donors and friends of the university. I discuss important issues with a wide array of people on virtually every significant campus issue.

On this [Salaita issue], I have heard from people who supported me, as well as those who criticized me. In coming to a decision, I was not influenced by any of them. My primary concern was for our students, the campus and the university

But this is what we know from FOIA documents not reproduced in the CAFT report:

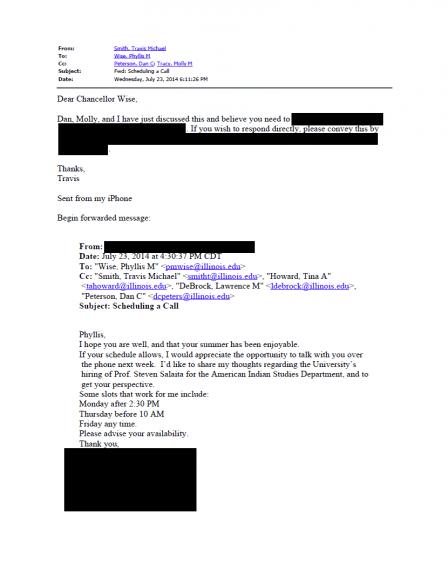

On Wednesday, July 23, 2014, Wise met with an unnamed outside individual whose sphere of influence we can only discern from the fact that she reported on the meeting the same day to heads of the office of the Vice Chancellor for Institutional Advancement (VCIA), which handles fundraising.

According to Wise’s report on this individual:

He said that he knows [redacted] and [redacted] well and both have less loyalty for Illinois because of their perception of anti-Semitism. He gave me a two-pager filled with information on Steven Salaita and said how we handle this situation will be very telling.

Also on July 23, Wise received an email from Steve Miller, a major donor to the University of Illinois, a member of the University of Illinois Foundation Board and its former chairman, and a board member of the UIUC Chancellor’s Strategic Advisory Board. Miller also happens to serve on the board of governors of UIUC Hillel and is a board member of the Jewish Federation of Chicago.

Miller’s email to Wise stated that he wanted

the opportunity to talk with you over the phone next week. I’d like to share my thoughts regarding the University’s hiring of Prof. Steven Salaita for the American Indian Studies Department, and to get your perspective.

For some reason, Miller cc’d this email to heads of the VCIA office as well as to the dean of the College of Business, for whom Miller has endowed several annual scholarships. An hour and a half after Miller sent his email, Travis Michael Smith, the senior director of advancement, emailed Wise concerning Miller’s letter, stating:

Dan, Molly, and I have just discussed this and believe you need to [passage redacted]

“Dan” refers to Vice Chancellor for Institutional Advancement Dan Peterson. “Molly” refers to Associate Vice Chancellor Molly Tracy.

Three hours after Smith’s partially redacted email to Wise, Wise emailed Miller, stating:

I am in Chicago on Friday and would like to meet with you rather than just talk over the phone, if you have time. I have meetings until 3:30 and my last meeting is in Evanston. I could be in your office in [redacted] by 4:00. Otherwise I would be happy to call you on Friday at 10:30 am between meetings that have been scheduled. For the moment, let me say that I just recently learned about Steven Salaita’s background, beyond his academic history, and am learning more now. [Passage redacted]. We are [passage redacted]

Subsequent emails between Miller and Wise detail efforts to establish a time to meet that would suit Miller, with Wise offering to “move a couple of meetings around.”

Contrast these communications with the CAFT’s interview with Wise, as described in the CAFT report:

[Wise] confirmed that she had not consulted with the Provost, the Dean of LAS [the College of Liberal Arts and Sciences], or other faculty representatives about her decisions not to forward Dr. Salaita’s offer of appointment to the Board of Trustees and to notify him in advance of this decision … She expressed much regret that she had not consulted more widely with the faculty and administration, and attributed her neglect of shared governance to the rapidity with which decisions had to be made.

The “rapidity with which decisions had to be made” did not deter Wise from conferring with the office of Institutional Advancement over Salaita, meeting with what appeared to be an influential donor over Salaita, and offering to “move a couple of meetings around” to meet with another influential donor in person to discuss Salaita, when that donor originally requested a phone meeting. All of these actions transpired before Wise informed Salaita of his termination on August 2.

As Corey Robin noted in his overview of the “Salaita Papers”—443 pages of FOIA documents from UIUC:

What’s most stunning about these documents is that they show how removed and isolated Chancellor Wise is from any of the academic voices in the university, even the academic voices on her own team. As she heads toward her August 2 decision to dehire Salaita, she is only speaking to and consulting with donors, alums, PR people, and development types …. [E]ven two days after the Chancellor has dehired Salaita, she still hasn’t informed the dean of the largest college at the UIUC of her decision.

The CAFT report gives no indication that the committee questioned Wise about many of these documents. Although it did not accept “the rapidity with which decisions had to be made” as a reasonable excuse for “her neglect of shared governance,” there is no indication that the committee quizzed Wise about her communications with the donors and VCIA staff specified above, of which we still only have limited information.

Moreover the CAFT report’s generous characterization of her violation of shared governance as mere “neglect” fails to account for the fact that within “the rapidity with which decisions had to be made,” Wise prioritized Salaita discussions with the VCIA office and with at least one or two donors, rather than with academic heads.

Thus it is irresponsible for Leibovitz and Tablet to claim, based on three sentences in the CAFT report, that “Donors Didn’t Derail Salaita Hiring” and that the donor issue is “one more wild canard being laid to rest.” Steve Lubet also misrepresents the report when he claims that it “puts the donor meme completely to rest” and that its statement of “no evidence” on the donor issue is “unequivocal.”

Such claims are not reflective of the report, either in wording or intent. According to Lubet:

The CAFT report is thorough and unbiased. It is also unsparing in its criticism of the chancellor (who submitted to an interview and made her emails available), so the conclusion about the absence of donor influence is especially reliable.

Yet as I have already demonstrated:

- The CAFT report might have been “thorough” in some respects, but clearly not in its investigation of the donor issue.

- Far from being “unsparing in its criticism of the chancellor,” it made the chancellor’s denial of donor influence the point of reference.

- Chancellor Wise did not “make her emails available.” They were made available through FOIA requests by outside parties—including myself—and they remain incomplete and partially redacted. Moreover, the emails reproduced in the CAFT report as “Document 10” were selected by the board of trustees counsel out of hundreds of pages of prior FOIA requests. These documents conveniently omit the more revealing emails that I have previously cited.

As well, there are still outstanding FOIA requests pertaining to Salaita that have prompted Salaita’s legal team to file a lawsuit to obtain.

The fact that the committee “found no evidence” in their investigation—but offer no detail of the extent of their investigation beyond Wise’s personal denial—is not proof that the donor issue is a red herring. Additional facts uncovered outside the committee’s purview demonstrate that this is a story still worth pursuing, and Wise’s denial does not close the door to this inquiry.

Are accusations of donor influence anti-Semitic?

On the suggestion that donors may have influenced the Salaita decision, Leibovitz writes:

One hardly needs to bother mentioning the noxious allusions such a claim evokes—a shadowy cabal of unnamed moneyed gentlemen exerting their will on the world.

And in an earlier article for Tablet, he wrote:

Those of Salaita’s defenders going for extra credit also hinted at the involvement of a cabal of unknown but deep-pocketed donors thwarting the hiring process with threats of defunding the school.

To the extent that these donors are “shadowy,” “unnamed,” and “unknown,” it is only because the FOIA requests have been redacted or are not forthcoming. But really, such colorful campfire stories are meant to suggest that charges of donor influence are anti-Semitic and thus outside the realm of legitimate discussion.

Is that a reasonable suggestion?

We can look at one very active and disturbingly influential Israel advocate, Tammi Rossman-Benjamin, of the Amcha Initiative and the so-called Scholars for Peace in the Middle East (and a one-woman “cabal,” if Leibovitz insists). In April 2014, Rossman-Benjamin wrote in the Jewish affairs news site Algemeiner that in order to fight criticism of Israel on college campuses, “Pressure must be brought from outside of the university”:

Information about faculty members who endorse BDS should be published and circulated widely. [Rossman-Benjamin published such a list in September.] Then, students, prospective students, alumni, parents, donors, and taxpayers should express outrage at the university’s collusion with an anti-Semitic campaign. Potential loss of student or donor revenue and the erosion of goodwill of the taxpaying public will send a compelling message to university administrators.

Rossman-Benjamin lays out this exact same strategy on page 232 of the book The Case Against Academic Boycotts of Israel, co-edited by the ubiquitous Salaita critic Cary Nelson.

Another of Nelson’s books, No University Is an Island: Saving Academic Freedom, makes clear that donor influence is a common problem in American universities:

[T]he ground has been prepared for still more aggressive political attacks on academic freedom from outside the university, from politicians demanding that faculty be fired to donors attempting to block controversial speakers on campus.

In the same book, Nelson recites stories of how the University of Illinois system has been manipulated by outside money and power. In one case, “UI chancellor Richard Herman was quietly conducting negotiations with donors” over the founding of a campus institute, whose inner workings were set forth in a secret Memorandum of Agreement that ceded “a disturbing level of authority over grants and appointments … to the outside donors, a fundamental violation of academic freedom.” As Nelson later explained,

Repeatedly, money and profit have trumped all other values, and those priorities have been embodied in administrative decisions by fiat that circumvented shared governance.

For the University of Illinois administration, Nelson wrote in 2010,

What is good, what is excellent, is money—not truth, not witness, not the public good, but money.

As Matthew Finkin and Robert C. Post write in For the Common Good: Principles of American Academic Freedom:

Universities and colleges may penalize politically outspoken professors to appease powerful interests – typically donors, trustees, or state legislatures – who are outraged by faculty expression … [I]nstitutions of higher education tend to believe that their reputation and support might suffer if they are associated with an “irresponsible” instructor.

Finkin is a member of the committee that issued the CAFT report.

The influence of money in academia is at the core of ongoing discussions about the “corporatization of the university” and of the “neoliberal university.” News reports about the billionaire Koch brothers’ attempts to influence academia abound. The idea that outside money and power has influenced campus administrative decisions is not new, nor should highlighting the existence of it be controversial. What should be controversial is that it happens, that it can go unquestioned, and that it should be rendered unspeakable under the pretext of countering anti-Semitism. It is the same baseless smear that set off the Salaita affair in the first place.

Conclusion

It’s important to understand that the CAFT report was deliberately worded, and efforts must be made not to paraphrase or add meaning or implications to the report that are not stated in the text. It is thus revealing that Jacobson, a professor of law, would be so sloppy in his reading of the report that he not only inserts unwarranted insinuations but also invents a quote from the report.

The value in the report extends only to the scope of its investigation and in its specified reasonings. On the bulk of the 41-page report, Leibovitz has little to say, dismissing much of it as “small illuminations” that “add up to little more than footnotes to the Salaita story,” while the three-sentence extract on donor influence “looms much larger.” Thus Leibovitz turns the report on its head.

This is expected, as the larger, more authoritative sections of the report ignored by Leibovitz challenge his claims in an earlier article, “Tweets Cost a Professor His Tenure, and That’s a Good Thing.”

This is the same Liel Leibovitz who wrote in Tablet magazine that the young Palestinian Mohammad Abu Khdeir, whose killing by Jewish Israelis was part of a series of events that precipitated Israel’s July 2014 Gaza invasion, was a victim of soccer, not “geopolitics”:

The truth is that Benjamin Netanyahu, the Palestinian Authority, settler rabbis and Hamas all have nothing to do with the terrible events that unfurled after six lowlifes forced a sweet-faced kid into their car and burned him alive. Soccer does. So please, enough with the ancient hatreds and the cycle of violence. The death of Muhammed Abu-Khudair is a terrible tragedy, but it’s not one unique to Israel. Anyone who watches soccer more frequently than a few matches every four years understands that intuitively.

After Leibovitz’s poorly argued thesis elicited criticism and ridicule, he doubled down with a follow-up article in Tablet, entitled “Soccer Fanaticism Leads to Violence Everywhere”:

A reasonable, critical-minded observer should have no problem accepting the possibility that a phenomenon prevalent in so many other western nations, from Sweden to Spain, could also occur in Israel.

The fact that Leibovitz is now seen by many of Salaita’s detractors as the leading judge of Salaita’s scholarship on the Middle East is only an indication of their lack of concern for truth and accuracy. Just as Salaita’s tweets have been twisted and manipulated, so has the ensuing affair.

A second article, forthcoming, will investigate other findings of the Salaita report.

Excellent piece of scholarship, Phan!

I read through it. There’s absolutely nothing new here in the way of evidence supporting the donor theory, which I sometimes like to call the “rich Jew theory,” because that’s essentially what it is. Phan actually spent several paragraph accusing Jacobson of “fabricating a quote” because he inadvertently transcribed “legitimate questions” as “legitimate concerns.” By the way, he corrected it here: http://legalinsurrection.com/2014/12/u-illinois-faculty-committee-fails-to-call-for-steven-salaita-position-restoration/

And as usual with Phan’s writing, he takes an inadvertent mistake like a misquote and ascribes a bad faith reason to it.

In any event:

1. Whether the Board cooperated with CAFT is totally immaterial. They have all denied that donor influence played any role in their decision, and they have done so repeatedly, including Montgomery. Phan says Montgomery’s statement is inconclusive; Phan can believe that if he wants, but it’s clear that Montgomery isn’t buying what Abunimah is selling.

As far as whether it’s antisemitic to suggest that donor influence played a role, it matters less than the fact that it’s simply not supported by the available facts, which is why we’re now hearing about “missing documents,” the last refuge of the civil lawsuit plaintiff who can’t prove his case. When you can’t prove a case, always create a blank slate onto which you can graft your wishes for what the evidence could be. Missing documents can say anything, so why not whatever Salaita wishes they said?

Frankly, Annie, the strongest arguments against Salaita’s nonhiring are the faculty governance arguments, the ones that assert that the Chancellor should have respected the decision of the Native American Students department and at least consulted with faculty before making the decision not to hiring Salaita, regardless of her reason why.

The donor theory has always been based on a couple of letters indicating that Wise met with a big pro-Israel donor – one – in a trove of some six dozen letters, the vast majority of which were expressions of dismay from current students, parents, and alums who were upset that the university would hire someone who said such things about Jews, and expressions of fear that Salaita would contribute to an unsafe atmosphere for Jews on campus. These the pro-Salaita campaign has studiously ignored.

A coterie of people, led obsessively by Ali Abunimah, have argued that donor influence was the reason Salaita wasn’t hired. It fits a narrative of rich pro-Israel Jews undermining Salaita’s appointment and a narrative of undue corporate influence in academia. Frankly, getting humanities professors riled up about their administrative bosses and corporate influence at colleges is like shooting fish in a barrel, and this issue with Salaita has been no exception. Believe or not, I have some sympathy for the faculty governance side of this question, even though I think that Salaita is the very rare case where the nonhiring was justified.

The problem with the donor theory has always been that there isn’t any real evidence to support anything other than that Wise met with this one donor guy about Salaita, which hardly makes the case that his appointment was derailed about nefarious donors. The proliferation of pro-Palestinian faculty, tenured and otherwise, on campuses across the country seems to vitiate the theory that pro-Israel donors could derail faculty hirings even if they wanted to.

Jacobson has corrected his misquotes, while claiming that it makes no substantive difference to my analysis. Waiting for Leibovitz to copy-follow.

I bet it does not make a difference for him.

RE: “The truth is that Benjamin Netanyahu, the Palestinian Authority, settler rabbis and Hamas all have nothing to do with the terrible events that unfurled after six lowlifes forced a sweet-faced kid into their car and burned him alive. Soccer does.” ~ Liel Leibovit

MY COMMENT: I’m not that knowledgable about soccer. Does it really involve killing people as human sacrifices?*

* SEE: “Abu Khdeir murder suspect recounts grisly killing”, by Daniel K. Eisenbud, JPost.com, 8/13/2014

ENTIRE ARTICLE – http://www.jpost.com/National-News/Abu-Khdeir-murder-suspect-recounts-grisly-killing-370911

Mr Nguyen is very thorough as I have noted elsewhere. He may wish to correct an error that was initially Corey Robin’s. August 1 not August 2 is the date that Chancellor Wise and Vice President Christophe Pierre wrote a letter informing Professor Salaita of his contract revocation. Twice this excellent piece has the wrong date.