My parents were divorced when I was six years old. Though it isn’t what drove them apart, my mother and father came from two different worlds.

My mother grew up on a farm in Kansas. My facial structure looks like hers (except my Arab nose), but it’s not easy to see because her features are much lighter than mine. She has red hair and blue eyes. In the past, my dark features and brown skin have led others to ask me if she was my adoptive mother. Guess that’s easier to believe than a mixed race family, huh?

My father was born in Jordan, to one of the most courageous women I’ve ever known. He was almost the youngest, with a difference of fourteen years between himself and one of his older brothers. My grandmother raised eleven children mostly on her own. Her husband died when my father was nine years old.

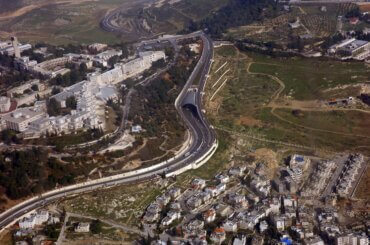

My grandparents were Palestinian, but were displaced more than half a century ago. Before the border was closed my family fled and built new lives in Jordan, a neighboring country. The Nakba of 1948 was a key part of my family’s history, so it’s difficult for me to believe that some people deny it happened. Nakba literally means catastrophe in Arabic, but the term is now almost exclusively synonymous with the massacre and displacement that happened in Palestine all those years ago.

Because of my mixed heritage, and because of the sense of displacement that naturally comes from being Palestinian, I have family members in many different countries. When I was younger, traveling at every opportunity was important to both of my parents, which is why I had the privilege to do so. This upbringing granted me some of my most invaluable memories— memories that are responsible for shaping a large part of who I am today.

My siblings and I spent most of our lives in Dubai, United Arab Emirates. Since my parents’ families were in different parts of the world, they took turns taking my siblings and me on summer vacations to different countries every year. My mother would take us to Kansas, or other states in the United States of America. My father took us to Jordan. (Some of my family returned to Palestine, integrating themselves into what eventually became Israel. Unfortunately, this isn’t an option for most Palestinians, especially those in the West Bank and certainly Gaza. It’s also more difficult now with segregation practices preventing Arabs from attending the same schools and often using different public transit as Jewish Israelis.)

On one of my childhood trips to Jordan, my father showed my siblings and me an olive tree that his brother had planted in Irbid outside of his house. My father went on and on about how fantastic this tree was, and how great it was that my uncle could grow olives. He talked about how he could eat and sell them, and press them into olive oil and eat and sell that, and so on.

Even though I was too young to understand economics and how ridiculous the idea of supporting yourself and a family with one tree was, I still thought my father was exaggerating the greatness of this olive tree. It was only a sapling. There wasn’t a single sign of fruit on it. Despite its inability to sprout one, it still carried the promising fragrance of olives.

This was one of many things I never really understood about my father. I just piled it away with a multitude of other things- other misunderstandings and discrepancies in our conversations. It didn’t bother me. For a long time, I forgot about it entirely. It was insignificant.

Throughout my upbringing, my father had read the Quran to us. In the Islamic faith, olives are considered sacred- a gift from God even. They are mentioned in the Quran at least three times from what I can remember.*

Even for non-Muslim Arabs, olives are ingrained in the culture. Most of our dishes contain olive oil. Even now, living with my sister in the United States, we eat olive oil almost every day. We use it as a seasoning, and we certainly don’t cook anything with vegetable oil. Most people attribute heavy use of the oil to the Italians, but it was us Palestinians that began the tradition.

Still, the importance of my uncle’s olive tree somehow eluded me until the trees were mentioned in a documentary I watched made by a Palestinian man who loved film. He called his documentary “Five Broken Cameras” because it took him that many to finish it. He replaced his equipment whenever he could, though some of the clips are still years apart. His name was Emad Burnat, and he was an olive farmer.

In his documentary, Burnat talked about his frustration when the Israelis claimed much of the Palestinian farmland, asking them “How will we make our living?”

Olive trees are quite resilient, and have the ability to thrive under harsh conditions. Culturally, we Palestinians see this as emblematic of our own strength. The oldest olive trees alive on this planet today still belong to us. Both the trees and the people who care for them are historically tied to the land.

It should go without saying that olives are also a staple in Palestine. A significant portion of the pre-occupation land was used for its agriculture. Much of that farmland was confiscated by Israel. Much of it was also destroyed. Most Palestinians (myself included) consider the latter to be far worse. Trees that families spent generations caring for were torn up from the ground. Their caretakers saw this as their age-old traditions and culture being pulled up and erased. It was a representation of what they had worked so hard to build for millennia being washed away. (I’m not joking. Some of the trees destroyed were that old.)

Lots of advocacy groups describe the Israeli army’s strategy of burning down our trees as “eco-terrorism,” but I don’t think any words can adequately describe the despair and the sadness caused by the loss of these thousands of acres. In the past, houses along the land were demolished and the people forced to leave. As a result of the occupation, there are ethnic Palestinians all over the globe: children and grandchildren of refugees who cannot forget where we came from. Despite how widely spread out we are, many of us will still encounter people that attempt to “educate” us about Palestine. They say “Palestine is a myth. Palestinians don’t exist.” Others are baffled to realize that “Palestinian” is an ethnicity, and not a religion. That there are Palestinians who are Muslim, Christian, Atheist, Agnostic, and even Jewish. Still, we make our lives where we can. I’m thankful that because of my mother, I have citizenship and the legal right to reside in the United States. Often I feel restless and want to travel again, but honestly, I don’t know where else I would go. I’ve often thought of Hawaii, Canada, Italy (where one of my uncles lived), and France (because I can speak a tiny bit of French.)

Even as I reflected on the impossibility of my ancestry, the significance of my uncle’s olive tree did not occur to me until I was much older. My father was not born in Palestine, but Jordan. Still, his older brothers remember Palestine. I don’t know if my family were originally olive farmers themselves. I also don’t know if they even had to be in order to remember the pain of those destroyed trees as the land was taken.

Now, I remember that time in Jordan when my father excitedly told me how my uncle brought seeds from Jerusalem and successfully grew a tree. I remember how he said “These will be Palestinian olives” and how inspired he was. That tiny, hopeful tree that I did not understand the meaning of- he saw as a symbol of our people trying to rebuild what we lost.

It makes me wonder what else we lost, that I filed away in other misunderstandings.

It’s been over ten years since that trip. Although I’ve been to Jordan since that time, I don’t think I noticed the tree or thought to try and find it. I haven’t seen it since, but I’d like to think that now it’s growing an abundance of those perfect, green, Palestinian olives.

* Here are a few links with English translations if you would like to see the Quranic verses in which olives are mentioned:

1) “Olives” in the Quran and Hadith–Medicinal and Nutritional Value from IqraSense

2) Sura Tin from AlSeraj (Note: “tin” in Arabic is pronounced “teen”)

(This was originally published on Amal alHazred’s blog under the title, “About Me: The Olive Tree.”)

Thank you so much for this lyrical post, Ms. AlHazred.

Thank you Amal

It’s only recently that I’ve been learning about the huge significance of olive trees to Palestinians and other indigenous people from the region both physically and symbolically. (mostly from a friend on MW). So when I hear about the settlers or the IDF destroying and burning trees they are also trying to destroy something much deeper; your intrinsic connection to the land itself. It’s just totally evil and so, so wrong on many levels.

5 broken cameras was a very emotional film to watch. The scene with the burning olive trees was truly horrific, not to mention the murders of the peaceful protesters. It’s a must watch film for anyone who hasn’t seen it and it’s free on YouTube I think

I hope we will hear a lot more from you.

Amal talks about the Zionists uprooting of the olive trees that are so national to Palestine and perhaps what was behind their obsession with destroying this landmark.

Ramzi Jaber with whom we are all familiar at Mondo is behind the Vizualizing Palestine campaign that put what the Zionists did to the olive trees in perspective and for that, his group used the example of NYC’s great and beautiful Central Park. The park cover 843 acres and contains 24,000 trees. The Zionist enterprise destroyed 800,000 Palestinian olive trees, which makes it 33 times the number of trees in Central park. 80,000 Palestinian families have been affected by the loss of livelihood from the olive trees that would have yielded over $12 million in annual revenue. There are still another 80,000 families living off the harvest but these too are seeing their trees gradually diminished each year by the settlers’ destruction.

Visit Vizualizing Palestine’s site for other great visuals:

http://visualizingpalestine.org/