THE POLITICS OF PERSECUTION

Middle Eastern Christians in an Age of Empire

by Mitri Raheb

207 pp. Baylor University Press, $24.99

Events in Ukraine have, curiously, turned a spotlight on Palestine and Israel—highlighting not just Israel’s delicate balancing act between Russia and the West but also exposing the history of Western colonial powers and their continuing effects in the region. Why, some are asking, has the West focused its resources, criticism and media attention on Russia’s occupation of Ukraine while, for the past fifty years, it has turned all but a blind eye to Israel’s occupation of Palestine? Why have Western powers so quickly turned to charges of war crimes against Russia when they have excused Israel’s incursions into Gaza and its often-brutal rule over Palestinians in the West Bank—what many human rights organizations are describing as apartheid?

The most recent book by Palestinian pastor, scholar and university president Mitri Raheb offers an answer rooted in a look at the interventions of Western powers in the Middle East. In short, as he shared during a recent lecture in Denver, Colorado, differing responses to the occupations of Ukraine and Palestine serve the West’s political and economic interests. In The Politics of Persecution: Middle Eastern Christians in an Age of Empire, Raheb tells an alternative, decolonial story of Western intervention, countering the prevailing accounts which shape foreign policy, media reports and common Western understandings.

“Christian persecution,” Raheb writes, “is a Western construct that says more about the West than about the Christians in the Middle East.” This central theme is developed throughout the book, exposing two realities. One, “the plight of Christians in the Middle East”—a common refrain in the West—is grounded in an orientalist perspective that sets a civilized Christian West against a barbaric Middle East considered “Islamic, irrational, anti-Christian, and stuck in a primitive mindset,” as Raheb writes. Two, over two hundred years this paradigm has served as a convenient pretext for political and military intervention in the Middle East, which interventions–neglecting the real needs of Christians—have contributed to their demise in numbers and to the few occasions of their actual persecution.

Raheb sets out to convincingly argue the book’s premise expressed in its concluding sentences: “Evangelical Christians and Western political forces want to frame the story of the Middle Eastern Christians as one simply of persecution. This study clearly demonstrates that the story is one of struggle, resistance, social involvement, and resilience.”

Raheb unfolds his argument by describing the gifts and the costs of Europe’s turning to the Middle East both as a source of raw materials—silk, cotton, olive wood, the famed Jaffa oranges—and a new market for European products. Increase in trade in the 1800s led to the creation of a merchant city-oriented culture, which led in turn to the importance of banking and education, which in turn led to consequential shifts in the agrarian, cultural and political life of the countries in the Middle East.

Europe’s economic interests were followed by the Western church’s interest in missions, fixed initially on making converts of Jews, Muslims and Eastern Christians. But when efforts at proselytizing failed, mission organizations turned from focusing on preaching and conversion to education and economic development. In his chapter, “Agents of Renaissance,” Raheb describes the work of these Western-sponsored Christian schools, writing, “It is not an exaggeration to claim that Christian schools shaped the entire Middle East.” Soon, however, Christians in the region recognized the colonial features of these European Christian missions and sought with varied success to gain greater independence from their Western benefactors.

In one of his most insightful chapters, “The Road to Genocide,” Raheb describes the colonization of the Middle East and the accompanying movements for nationalism that followed the breakup of the Ottoman Empire. “European penetration into the Middle East,” he writes, “brought not only modernization, education and renaissance, but also Zionism, nationalism, and ultimately, colonialism. These three elements of the nineteenth-century European encounter with the Middle East were seeds for future conflicts in the region.”

The heart of the chapter describes one of the most egregious acts of genocide in the 20th Century: the massacre of the Armenians. Here, Raheb makes a convincing case for his argument that, in spite of their oft-repeated concern about “the persecution of Christians,” Western powers have always been more concerned about their national interests—even when there is an enormous cost to be paid by the Christian communities they purport to protect. World War I gave sufficient cover for the most extreme political party of the Ottoman Empire to carry out its plan to keep the proportion of non-Muslim and non-Turks (Armenians, Assyrians and Greeks) to under ten percent. Readers will learn how “Christian” Germany, the Ottoman Empire’s only ally—and Emperor Wilhelm II, a pious Christian and, as King of Prussia, head of the German Protestant Church—were complicit in the Armenian Genocide. Raheb writes, “Western empires were never really interested in the Middle Eastern Christians but sought a pretext to promote their imperial interests. In most cases [of Western intervention] the West was part of the problem for Middle Eastern Christianity and not part of the solution.”

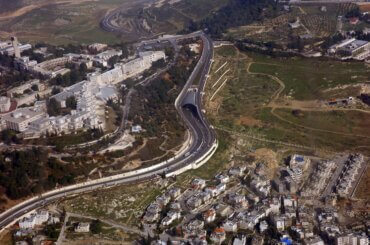

In his chapter on the 1967 War, “A Turning Point,” Raheb continues to fulfill his promise to describe the effects of global events, not just on Christians in Palestine, but on the entire Middle East. Readers are reminded how the war led to regime change throughout the region: Iraq in 1968, with Saddam Hussein coming to power; Libya and Sudan in 1969, with Qaddafi and Nimeiry, respectively, taking power; Syria in 1970, with Assad; and the death in 1970 of Egypt’s Abdel Nasser. Change came in Israel, too, as extremist Jewish groups started settling in the West Bank and Judaizing what they described as “Judea and Samaria.” As one might expect, Raheb devotes a significant portion of his book to describing, from a Palestinian perspective, the West’s part in the formation of the State of Israel, what Palestinians call the Nakba (Catastrophe). There’s much to learn here, even for those well-acquainted with the events leading up to 1947 and its consequences.

There’s much more in the book: a look at the diversity of the Christian community throughout the Middle East; unique takes on the consequences of Christian Zionism; the effects of the West’s dependence on Middle Eastern oil; accounts of Middle Eastern Christians contributions to the education, culture and political life of their countries in greater measure than their numbers might suggest; and the causes and effects of Palestinian Christian emigration.

The final chapter, “Challenging Times,” is worth the price of the book. Raheb explores “ten main challenges facing the region as a whole that will determine its fate and ultimately the future of its Christians”: population growth; continuing conflict and war; failure of the rule of law in many places; state security versus human security; management of human and natural resources; the relationship between religion and state; the role and potential of youth; the challenges facing women; climate change; and the growing demand for human dignity across the region.

In The Politics of Persecution, the Rev. Dr. Mitri Raheb, founder and President of Bethlehem’s Dar al Kalima University and author of more than forty books, has delivered an informed and nuanced description of the social, economic and geopolitical realities that have given rise to the persecution of minorities throughout the Middle East, not just Christians. He has given lie to the portrait of a church at the mercy of its Muslim neighbors and witnessed, instead, to the extraordinary resilience and strength of the Christian community. He writes,

Over a period of two millennia, Middle Eastern Christianity survived one empire after the other by developing great elasticity in adjusting to changing contexts. Christians learned how to survive atrocities and how to resist creatively while maintain a dynamic identity… contributing to their communities and advocating for neighborly relationships, equal citizenship, and open, tolerant, and pluralistic societies.

While written for a general audience, a rich bibliography and thorough index will aid the Middle East scholar who will no doubt turn to the book many times.

During his lecture in Denver, Raheb said, “If the major powers would help us have peace in our region, there would be no persecution. If the Empires would help us have some stability, there would be better conditions for Christians, for Muslims, for Jews, for everyone.” For those of us in the West, we might take his comment—along with his book—as something more than a scholar’s observation.

Thanks to Peter Makari and Don Wagner for sharing their insights on The Politics of Persecution which contributed to this review.

A great book. Christianity, Judaism and Islam paid a heavy price for what happened in Palestine over the past 100 years. Will it be that through their sincere collaboration, being traced to same source, that helps reverse the tide in the next hundred?

‘Christian persecution’ may be a Western construct, but how then should we conceptualize the relations of traditional Moslem regimes with their Christian and Jewish minorities before the penetration of Western colonialism? Did they have equal status? Were they treated in the same way as Moslems? ‘Persecution’ may be a misleading word, but how about ‘subordination’ or ‘stigmatization’? Were they not required to pay a special tax and was its payment not associated with humiliating rituals? Did they have the same right as Moslems to bear arms? To ride a horse and not just a donkey? Were they not required to wear identifying clothing? Such practices were not universal but they were fairly widespread. Was the professed concern of European Christians and Jews with the position of their co-religionists in the Moslem world in all cases insincere, never more than a tool of geopolitics? Did it always make their situation worse? (I can believe that if often did.)

In general, I am suspicious of works in which the first object of investigation is a ‘narrative.’ It is better for truth and sanity that first of all we undertake an assessment of reality, and only on that basis proceed to a critique of narratives.

This recurring whine, why is the west concerned with Ukraine and not Palestine is getting a bit tired. The west is concerned with power and freedom. Would palestine be free? Would it be powerful? It is a tiny corner of the world, whose claim to fame is holy places and the fact that the Jews want to live there. otherwise it is a backwater nowhere podunk nothing place. Ukraine is a breadbasket of europe, a large country and it is a poke in russia’s side. and the west has been struggling with russia since napoleon. to a chess player this complaint why ukraine and not palestine is simple, it isn’t about pure motives, it’s game of power. and in the battle for democracy a democratic ukraine is an accomplishment, a palestine led by a corrupt decrepit group of has been revolutionaries or a palestine led by islamic imams just adds nothing to the world. this palestine that has backed every anti democratic anti western force for the last 100 years. what would it add to the world? not much. i grant that the palestinian people want their freedom and that this desire is not going to be quieted. but this incessant whining. “oh you hypocrites, you hypocrites.” i guess whining is better than blowing up pizza places, so I shouldn’t complain. but this incessant whining. genug schon.