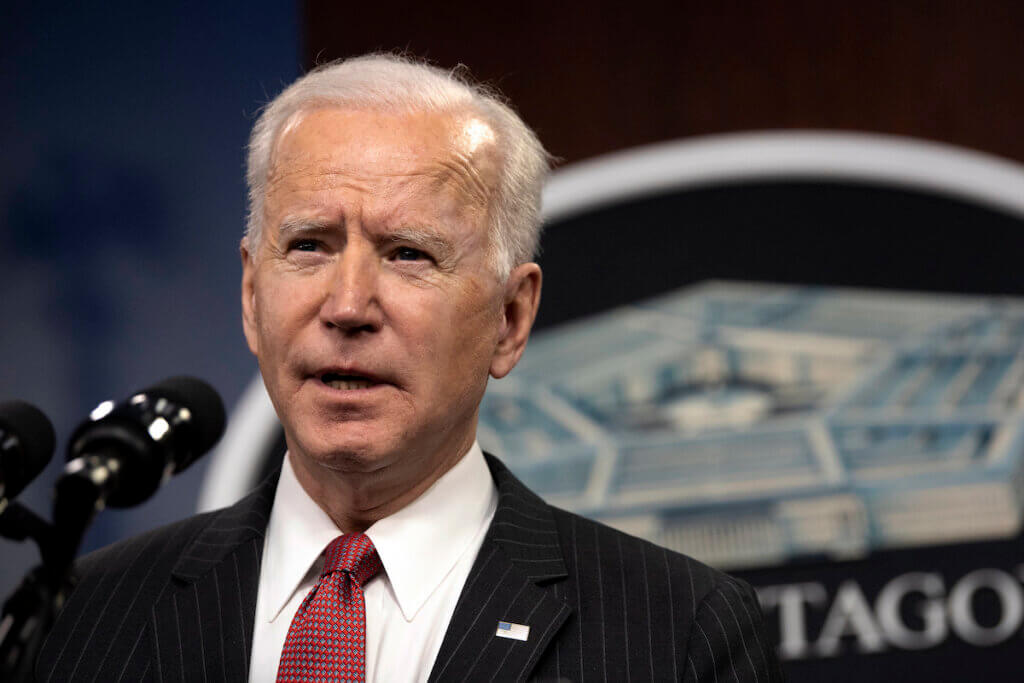

There have been mixed reactions to the Biden Administration’s decision to place economic and travel-based sanctions on four Israeli settlers on Thursday, February 1. Some have been cautiously optimistic that the sanctions—which came in the form of an Executive Order—would bring long-absent accountability for Israeli settler violence in the West Bank. Others have criticized the sanctions as a cynical move to whitewash the Biden Administration’s own crimes and win over disillusioned Arab, Muslim, and Palestinian voters, whose support for Biden has substantially plummeted as a result of his unwavering support for Israel’s onslaught on the Gaza Strip.

There is no doubt that meaningful accountability for Israeli settlers is urgent and necessary. The Biden Administration first floated the idea of sanctioning Israeli settlers in mid-November, as the Israeli military and settlers meted out the worst violence in the West Bank since the Second Intifada. Under the cover of Israel’s military campaign in Gaza since October 7, 2023—a campaign the International Court of Justice recently described as constituting a “plausible” risk of genocide—Israeli settlers and the Israeli military, which often work closely together, have killed nearly 400 Palestinians, including over 90 children, in the occupied West Bank and East Jerusalem. Mass displacement of Palestinians—including at the hands of settlers—has also spiked since October 7, with the goal of consolidating permanent Israeli control over even more Palestinian land. In the last four months, Israeli settler and military violence has displaced approximately 198 Palestinian households, encompassing over 1200 people.

The surge in Israeli settler violence did not begin on October 7. In the first eight months of 2023, the UN documented approximately three incidents of settler violence in the West Bank every day—the then-highest level of settler violence recorded by the UN since it began gathering such statistics in 2006. Throughout 2023, settlers rampaged across the occupied West Bank and East Jerusalem, killing and terrorizing Palestinians, displacing them from their homes, and destroying their property. Israeli settler violence against Palestinians has been a long-standing feature of Israel’s settler-colonial policies. As Israeli human rights organization B’Tselem has described it, “[s]ettler violence against Palestinians serves as a major informal tool at the hands of the state to take over more and more [Palestinian] land. . . .settler violence is a form of government policy, aided and abetted by official state authorities with their active participation.”

Unfortunately, Biden’s Executive Order is unlikely to meaningfully address the scourge of Israeli settler violence. This is not just because of a lack of political will. Rather, it is also because the sanctions order, itself, is written narrowly in ways that circumscribe its impact on settler violence, while at the same time is written so broadly it can be used against Palestinians. Indeed, the Executive branch will almost certainly use the order against Palestinians, perhaps even disproportionately so.

Too narrow to address Israeli settler violence

The Executive Order is narrow because, while it applies to the West Bank, it is unclear whether it also applies to East Jerusalem. Though the United States officially considers East Jerusalem to be occupied by Israel, its statements about and policies towards East Jerusalem suggest it unofficially supports Israeli sovereignty over the occupied city. At the very least, the U.S. government seems to consider East Jerusalem to be separate from the West Bank. On top of this, given Israel’s position on East Jerusalem—which it unilaterally annexed in contravention of international law in 1980 and considers part of its undivided capital—it is unlikely the Biden Administration or any other presidential administration will be willing to extend the Executive Order’s ambit to this territory. This omission, of course, means a crucial and important site of Israeli settler violence remains beyond the Executive Order’s reach. As part of their efforts to demographically dominate the city, the Israeli state and its settlers have been particularly keen on reducing, if not eliminating, the Palestinian presence in East Jerusalem, through both legal and extra-legal, violent means.

Further narrowing Biden’s Executive Order is the fact that it only sanctions “foreign persons.” While Americans must comply with sanctions against such foreign persons, U.S. persons are not directly subject to Biden’s order. Again, this significantly limits the Executive Order’s scope. By excluding Israeli-American settlers from its effects, the order fails to cover a community that is reportedly “leading” the rise in settler violence against Palestinians.

Broad enough to target Palestinians

At the same time, the Executive Order is quite broad and goes beyond the government’s stated concerns with settler violence. The word “settler” is only mentioned once—in the preamble to the Executive Order—and, even then, is used simply to note that “the situation in the West Bank — in particular high levels of extremist settler violence, forced displacement of people and villages, and property destruction — has reached intolerable levels and constitutes a serious threat to the peace, security, and stability of the West Bank and Gaza, Israel, and the broader Middle East region.” That is it. That is the only reference to settlers in the Executive Order—in what effectively amounts to a non-exclusive list of concerns that purportedly led the administration to create the sanctions order. Notably, the Executive Order neither describes the settlers as Israeli nor does it mention, at any point, that the forced displacement of “people and villages, and property destruction” is happening to Palestinians.

The breadth of the order is also reflected in its application to “foreign persons” writ large, as well as to non-violent peaceful activity. As a result, the Executive Order applies, on its face, to both Israelis and Palestinians (as well as other non-U.S. persons) who are not engaged in any violence. For example, the order sanctions foreign persons “directing, enacting, implementing, enforcing, or failing to enforce policies — that threaten the peace, security, or stability of the West Bank” and could be applied to Palestinians and their Israeli allies who engage in peaceful acts of civil disobedience to protest the on-going dispossession and subjugation of Palestinians by Israel’s occupying forces. Similarly, the order sanctions “leaders or officials” of “an entity, including any government entity, that has engaged in, or whose members have engaged in…” actions threatening the peace, security, or stability of the West Bank. This could be applied to Palestinian Authority officials who pursue peaceful policies or actions that, for example, challenge Israel’s continued military presence inside the West Bank. Another part of the order sanctions foreign persons who “have materially assisted, sponsored, or provided financial, material, or technological support for, or goods or services to or in support of, any person blocked pursuant to this order.” This means that, if a foreign person–for example, a French citizen living in France–provides money to a Palestinian civil society group that is blocked under the Executive Order for their peaceful activities, that person could be sanctioned themselves. Even though U.S. persons cannot be sanctioned under the Executive Order, they could still be subject to criminal and civil penalties for violating the order when they make contributions or provide goods, funds, or services to sanctioned persons—including to sanctioned Palestinians.

In deciding who else to list under the order, the Executive branch has a great deal of discretion. Indeed, important components of the order—like what constitutes a “threat” to the “peace, security, or stability” of the West Bank—are not defined and therefore left up to Executive Branch officials to interpret—something they are likely to do, as they often do in these situations, without sharing their interpretations with the public at large. Nor is it likely that U.S. courts will intervene to question Executive Branch decisions as to which persons should be subject to the order’s sanctions regime, as they have rarely done so in the past.

The Biden Administration could have explicitly drafted the Executive Order to apply only to Israeli settlers—it has issued countless sanctions orders in the past that have targeted foreign persons based on their nationality. The only reason for the Biden Administration not to do this here is to ensure Palestinians would also be covered—as suggested by another recent policy move by the government.

In early December, the Biden Administration established new visa restriction rules targeting those “undermining peace, security, or stability in the West Bank.” While the policy’s announcement specifically references Israel’s failure to address settler violence against Palestinians, it also makes clear that the new rules are directed at both Israelis and Palestinians. In mirroring the same policy objectives as last week’s Executive Order, the government’s visa restriction policy speaks volumes about the administration’s strategy here as well—namely to appear as if it is punishing Israelis when, in fact, it is punishing Palestinians too.

An anti-Palestinian precedent

Biden’s Executive Order will likely be disproportionately used against Palestinians, in line with other past and on-going U.S. government practices towards Palestinians. These past practices include an Executive Order issued in 1995 by President Bill Clinton, sanctioning groups threatening the so-called “Middle East peace process.” Upon its issuance, the order included a list of twelve sanctioned organizations, ten of which were Palestinian, Arab, and/or Muslim, and only two of which were Jewish Israeli. One might argue that this distribution simply reflected the then-existing threats to “Middle East peace.” That is, however, a highly unlikely diagnosis, given the on-going nature of Israeli settler violence over the course of the last forty years—violence that was turned against Israeli Prime Minister Yitzhak Rabin, who was assassinated by a dedicated Jewish Israeli believer in the continuation of the Israeli settlement process on Palestinian land only ten months after Clinton’s Executive Order.

The Clinton order is but one example of the pervasive, long-standing tendency of U.S. officials to center all blame on the Palestinians and to privilege and bolster Israeli interests. Indeed, U.S. law is littered with examples of consistent, persistent government-sanctioned discrimination against and dehumanization of Palestinians, both explicitly and implicitly. There is no reason to think Biden’s Executive Order will be implemented—either by him or by future presidents—in ways that eschew this historical legacy. Pro-Israel advocates are also likely to take advantage of this order to push the government to sanction Palestinians in the West Bank—furthering its likely disproportionate impact on Palestinians.

So what is the solution here? One strategy is to urge the administration to revise the order to only focus on Israeli settlers, while also expanding it to explicitly include East Jerusalem as well as American-Israeli settlers (U.S. persons can be subject to sanctions, even though they benefit from constitutional protections that foreign persons do not). On the other hand, sanctions are a blunt tool that have a dubious legacy of changing the behavior of targeted states, entities, and individuals. To truly end Israeli settler violence, Israeli settlers themselves need to be removed from occupied Palestinian territory. That is the only real solution here—and one the U.S. government has significant power to achieve.